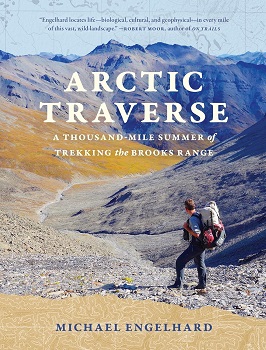

Arctic Traverse: A Thousand-mile Summer of Trekking the Brooks Range by Michael Engelhard

Warning: reading Arctic Traverse: A Thousand-mile Summer of Trekking the Brooks Range by Michael Engelhard may cause you to fall in love with Alaska’s Brooks Range – and also to dream about being pursued by grizzly bears. Engelhard is an evocative writer, and Arctic Traverse is very much his love letter to this wild, remote place. Yes, he encounters many grizzlies on his solo walk across the Brooks Range.

The overland on-foot part of Engelhard’s journey starts at Joe’s Creek in the northeastern corner of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and angles southwest through the heart of the Brooks Range, passing through Gates of the Arctic National Park; the journey finishes canoeing the Noatak River to its outflow at Kotzebue.

Engelhard’s day-by-day narrative weaves together layers of stories contained within the land: the lives of Native people for whom the land has been sustenance since time immemorial, explorers, entomologists and geologists, naturalists who studied the area’s wolves, caribou and lichen, as well as the author’s own memories from previous trips.

And what an incomparable land the 700 mile long, 150-mile-wide Brooks Range is: Engelhard notes that the area has few Alaska Native place names almost “as if this corrugation of space in its totality were beyond contemplation.”

The Brooks Range exists within the unparalleled rich ecosystems of both the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve. Each year, ANWR hosts 180 bird species from every U.S. state and six continents, 45 mammal and dozens of fish species. Gates of the Arctic is the northernmost and second largest U.S. National Park, championed into creation by Robert Marshall, a John Muir-like character who advocated for protecting this land, urging Congress in 1938 to “keep Alaska largely a wilderness.”

Through tussocked areas and difficult country, Engelhard’s only companions were the region’s flora and fauna, weather and ever-changing vistas. He learned that it pays to follow mammalian paths, like the well-beaten caribou herd migration routes as they move to summer grazing and calving areas.

During his overland journey, on average, Engelhard encountered grizzlies every other day. Most scampered away after scenting him, but after 10 days and no bear sightings in Gates of the Arctic National Park, a grizzly appeared suddenly, locking eyes and beginning to follow him. Was the bear testing his response, looking for signs of weakness or poor health? Ruminating on the ecological value of weeding out the unfit in a herd to preserve the strongest in the gene pool is no solace while being followed by such a predator.

Swarms of the ubiquitous Alaska mosquitos torment humans and animals alike, enough to send herds of caribou stampeding or drive moose to forego food and simply stand neck deep in lakes for days at a time. Entomologists estimate Alaska mosquito density at 5 million adult mosquitos for every acre of land. A naked person outdoors during peak bug season could become anemic after 11 bloodsucking hours and bled-dry after another 11 hours.

Setting up camp early one day, Engelhard watched arctic terns fishing. Terns, whose migration chases the sun from the Arctic Circle to Antarctica, may, in a lifetime, travel the equivalent of three round trips to the moon, and have been poetically described as “little more than a heart enclosed in wing muscle.”

Seven weeks to the day after setting off on foot from Joe’s Creek, Engelhard reaches his final cache at the Noatak River, which includes the inflatable canoe in which he will pilot his way to the town of Kotzebue just north of the Arctic Circle on the Chukchi Sea.

The final leg of the journey is a 7-mile paddle across Kotzebue Sound where the waters of the Noatak return to the sea, known for high winds that can capsize boats. Eager to complete the journey and brain-addled from lack of sleep, Engelhard underestimates the offshore wind and finds himself off-course and getting blown out to sea. Luckily, he manages to flag down a fishing boat and three Inupiat fishermen deliver him to Kotzebue on the far shore.

Throughout Arctic Traverse, Engelhard champions those who have dedicated their energy to protecting this wild land – and cautions the rest of us about what we are in danger of losing. The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the globe, melting permafrost, changing forested areas, shrinking tundra and threatening extinctions.

This delicate ecosystem is also strained by more people traveling to the area to experience what Engelhard deemed the lure of “beauty, sanity, wisdom, and wholeness.” A highly recommended read for those interested in learning about Alaska wilderness natural history and conservation, Indigenous cultures and solo trekking.

Lisa Gresham is collection services manager at Whatcom County Library System; visit wcls.org to learn more about The Power of Sharing.

(Originally published in Cascadia Daily News, Sunday, July 21, 2024.)